The Silent Loneliness Epidemic Nobody Talks About

Loneliness is linked to an estimated 100 deaths every hour more than 871,000 deaths annually. This staggering mortality rate rivals or exceeds deaths from smoking, obesity, and many major diseases, yet loneliness remains largely invisible in public discourse. The U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy has called it a “national epidemic of loneliness and isolation,” something that can have profound effects on sufferers’ physical and mental health. Loneliness is impacting one in six people worldwide, with significant impacts on health and wellbeing, according to a new report from the World Health Organization.

Recent data reveals the crisis is intensifying. AARP’s most recent study on loneliness shows that 40% of U.S. adults age 45 and older are lonely, a significant increase from 35% in both 2010 and 2018. Between 17-21% of individuals aged 13 to 29 reported feeling lonely, with the highest rates among teenagers. The loneliness epidemic is shaped by shifting social landscapes where adults in their 40s and 50s are especially vulnerable, facing unique pressures such as work stress, caregiving responsibilities, and changing family dynamics. Men now report higher rates of loneliness than women (42% vs. 37%), a shift from the 2018 gender parity.

The paradox is striking: we live in the most connected era in human history with instant global communication, yet we’re experiencing unprecedented levels of loneliness. The silence around this epidemic stems partly from stigma, partly from its invisibility compared to physical ailments, and partly from collective denial about the consequences of modern lifestyle choices. Understanding this silent crisis requires examining why it’s happening, who it affects, how it damages health, and why society remains reluctant to confront it openly.

Why Loneliness Is Epidemic and Accelerating

According to research, beginning at the turn of the 19th century, industrialization reduced social connectedness and spawned loneliness. This problem has exploded over the past couple of decades, with doubling of the prevalence of loneliness. A study found that 76% of adult Californians suffered from moderate to severe loneliness, which was associated with worse physical, cognitive, and mental health. The trajectory shows not just high baseline loneliness but accelerating increase suggesting underlying causes are intensifying rather than stabilizing.

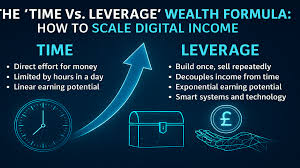

Multiple factors are responsible for this unprecedented worldwide rise in loneliness, suicides, and opioid use during recent years. While direct causality is difficult to demonstrate, there is probably a common underlying thread of social anomie and disconnection resulting from the incredibly rapid growth of technology, social media, globalization, and polarization of societies. Although technology and globalization have improved quality of life in many ways, they have also upended social mores and disrupted traditional social connections.

Information overload, 24-hour connectivity, countless but superficial and sometimes harmful social media relationships, and heightened competition have elevated the level of stress in modern society. A recent Gallup poll reported a 25% increase in self-reported stress and worry in the U.S. over the past 12 years. The chronic stress created by modern life both contributes to loneliness directly and depletes the psychological resources needed to maintain meaningful connections, creating vicious cycle where stress causes isolation which increases stress.

Loneliness and social isolation have multiple causes including poor health, low income and education, living alone, inadequate community infrastructure and public policies, and digital technologies. The report underscores the need for vigilance around the effects of excessive screen time or negative online interactions on the mental health and wellbeing of young people. About 24% of people in low-income countries reported feeling lonely, which is twice the rate reported in high-income countries (around 11%). This suggests that economic insecurity and lack of community resources compound loneliness beyond the technological factors affecting wealthier nations.

Shrinking Social Circles and Declining Community

A shrinking social network is one of the strongest predictors of loneliness. Nearly half of lonely adults have limited social resources and wish for stronger connections, compared to about a third of adults overall. Community engagement is also declining where fewer people are attending religious services, volunteering, or joining local groups. As opportunities for connection diminish, adults—especially those who are lonely—are spending more time alone, with lonely adults averaging 7.3 hours alone each day compared to 5.6 hours for the overall 45-plus population.

Research shows we’re spending less time with friends, we’re spending less time with family, and we’re not volunteering as much as people were decades ago. But there are also broader demographic trends that contribute to social isolation. People are living farther from their families than they did in the past. People are having fewer children. Marriage rates are down. When we look at trends in social connections and social isolation, these structural changes create environments where loneliness becomes default rather than exception.

The institutions that historically provided community connection have weakened or disappeared. Religious congregations that once served as social hubs for millions see declining attendance. Civic organizations like Rotary Clubs, Lions Clubs, and similar groups have lost membership. Neighborhood connections have frayed as people spend more time commuting, working, and engaging with screens rather than neighbors. The workplace, once a source of daily social contact, has become more transactional and remote, especially post-pandemic with widespread adoption of work-from-home arrangements.

The decline in face-to-face “third places”—locations besides home and work where people regularly gather informally—has eliminated crucial social infrastructure. Coffee shops increasingly feature isolated individuals on laptops rather than groups in conversation. Parks, libraries, and community centers see reduced use as people opt for home entertainment. The built environment of suburbs and car-dependent development patterns physically separates people, requiring deliberate effort to see others rather than encountering them naturally through daily activities.

The Profound Health Consequences

The impact of social disconnection extends beyond individual health, with research estimating that loneliness costs employers around $3.2 billion annually due to reduced productivity and staff turnover. Emerging UK evidence suggests that loneliness may be causally linked to at least six diseases, including hypothyroidism, asthma, depression, psychoactive substance misuse, sleep apnea, and hearing loss. An annual mortality of 162,000 Americans is attributable to social isolation, exceeding the number of deaths from cancer or stroke.

Loneliness increases the risk of heart disease and stroke, similar to well-known risks like smoking and obesity. Isolated individuals are more vulnerable to infections and illnesses, as loneliness can trigger inflammation and hinder the body’s defenses. Loneliness is a major risk factor for depression, anxiety, and even thoughts of self-harm. Studies indicate that loneliness may speed up cognitive decline and increase the risk of dementia. There is some evidence to suggest that isolation is more predictive of physical health outcomes, whereas loneliness is more predictive of mental health outcomes.

Longitudinal investigations have shown that loneliness is a risk factor for generalized anxiety disorder, major depression, and dementia. Determining the underlying processes is critical for identifying targets for preventing psychiatric morbidity in lonely individuals. The high medical comorbidity and mortality raise the possibility of loneliness resulting in accelerated biological aging, as has been postulated for serious mental illnesses like schizophrenia in which loneliness is especially common. Postulated mechanisms for accelerated aging including inflammaging and oxidative stress should be explored in persons with loneliness.

Strong social connections can lead to better health outcomes and reduced risk of early death. The flip side is equally true where lack of connection creates health risks comparable to major lifestyle factors that receive far more public health attention. The mortality impact of loneliness rivals smoking, yet while smoking receives massive public health campaigns, warning labels, and policy interventions, loneliness remains largely unaddressed despite killing comparable numbers of people annually.

The Psychological Mechanisms of Chronic Loneliness

The importance of loneliness is under-recognized and undervalued, and it poses a major risk for health outcomes and quality of life. Loneliness is stigmatizing, causing people to feel unlikable and blame themselves, which prevents them from opening up to doctors or loved ones about their struggle. At the same time, healthcare providers may not think to ask about loneliness or know about potential interventions. The stigma creates silence where those suffering most are least likely to seek help or even acknowledge the problem.

Research concluded that it is dysregulated emotions and altered perceptions of social interactions that have profound impacts on the brain, suggesting that people who are lonely may have a tendency to interpret social cues in a negative way, preventing them from forming productive positive relationships. Results are consistent with the idea that loneliness is associated with negative biases about other people. If we expect negative things from other people—for instance, that they cannot be trusted—then that would hamper further social interactions and could lead to loneliness.

This creates vicious cycle where loneliness alters perception making social cues seem more negative and threatening, which causes withdrawal and defensive behavior, which creates actual negative social experiences, which reinforces negative expectations. Breaking this cycle requires addressing the distorted cognitions and negative biases, not just providing opportunities for connection. While just giving people the opportunity to connect may work for some, others who are experiencing really chronic loneliness may not benefit very much from this unless their negative belief systems are addressed. Some sort of psychotherapy may be helpful in this situation.

Loneliness is both a subjective state and a personality trait determined by genetics and hormonal and cerebral pathophysiology. This suggests that for some people, loneliness has biological underpinnings beyond just circumstances, making it a more intractable problem requiring medical or therapeutic intervention rather than simple social prescription. The complexity of loneliness—operating at biological, psychological, and social levels simultaneously—makes it challenging to treat and explains why simple solutions often fail.

Why This Epidemic Remains Silent

Despite its prevalence and severity, the loneliness epidemic remains largely undiscussed in public conversation. The stigma associated with loneliness creates profound silence where admitting loneliness feels like admitting fundamental unlikability or social failure. In a culture that values independence, self-sufficiency, and popularity, loneliness represents personal inadequacy rather than systemic problem. This stigma prevents people from discussing their loneliness openly, making the epidemic invisible despite affecting enormous portion of population.

The survey found that societal division may have intensified feelings of loneliness, and it could have a measurable impact on health and wellbeing. Political and social polarization creates environments where people retreat into ideological bubbles and view those outside their group with suspicion or hostility. This fractures potential connections across differences and creates loneliness even among those surrounded by others. When society is divided, the scope for finding common ground and shared humanity shrinks, leaving people feeling isolated even in crowds.

There is also a well-documented loneliness epidemic affecting not just young people, but middle-aged adults as well—those juggling work demands, caregiving responsibilities, and the erosion of long-term friendships. The middle-aged are particularly silent about loneliness because they’re supposed to be established in careers, families, and communities, making admission of loneliness feel especially shameful. Yet this demographic faces unique pressures that destroy social connections including demanding careers, caring for both children and aging parents, geographic mobility for work, and the fading of friendships from earlier life stages.

The invisibility of loneliness compared to physical ailments makes it easy to ignore. Unlike broken bones or cancer, loneliness leaves no visible marks. Healthcare systems focus on measurable physical conditions while overlooking subjective emotional states. Social policies address poverty, education, and employment while neglecting social connection. The UK stands out as one of the few high-income countries to have already embedded actions against loneliness and social isolation into national policy. Most countries lack even basic recognition of loneliness as public health priority requiring intervention.

Generational and Demographic Patterns

The findings suggest that loneliness is affecting people of all ages, especially adolescents and people living in low- and middle-income countries. Those at the younger end of the 45-plus spectrum experience the highest rates, while loneliness tends to decrease with age, higher education, and greater household income. This pattern contradicts assumptions that elderly people are loneliest, revealing that young adults and middle-aged people face intense loneliness despite being digitally connected and often surrounded by others in cities and workplaces.

The high rates among teenagers and young adults are particularly concerning given the long-term health consequences of early loneliness. Adolescence is critical period for social development, identity formation, and establishing patterns of connection. Loneliness during these formative years can set trajectories of isolation, poor mental health, and inability to form deep relationships that persist into adulthood. The normalization of digital rather than face-to-face connection for this generation may be creating cohort that never develops skills for deep human connection.

Men now reporting higher rates of loneliness than women represents significant shift with important implications. Traditional masculinity norms discourage emotional vulnerability and seeking help, meaning lonely men are even less likely than lonely women to acknowledge the problem or seek support. The male tendency toward smaller social networks focused on shared activities rather than emotional intimacy makes men particularly vulnerable when life changes disrupt those activity-based connections. Work retirement, geographic moves, or relationship breakdowns can leave men suddenly isolated without the emotional intimacy skills to rebuild connections.

The socioeconomic gradient in loneliness where it’s more common among those with lower income and education reveals that loneliness isn’t just psychological or technological issue but also structural problem related to economic inequality and access to resources. Poor neighborhoods with inadequate community infrastructure, long work hours with multiple jobs limiting social time, inability to afford social activities, and economic instability preventing relationship investment all contribute to higher loneliness among economically marginalized populations.

Potential Paths Forward

Healthcare providers need to be more aware of loneliness as a health risk factor, try to identify people at risk, and think about how best to support them. This requires incorporating loneliness screening into routine healthcare visits similar to how depression screening has become standard. Medical professionals need training to recognize loneliness, understand its health implications, and make appropriate referrals for interventions. The medicalization of loneliness—treating it as legitimate health condition rather than personal failing—could reduce stigma and enable systematic response.

While social media is often blamed for making people feel more alone, a handful of new apps are trying to help people make new connections. Technology designed specifically to facilitate face-to-face meetings and shared activities rather than virtual connections might help reverse some of the isolation technology has created. However, addressing loneliness through technology remains paradoxical given technology’s role in creating the problem, and such solutions likely work best as bridges to real-world connection rather than destinations themselves.

The report serves as a critical call to action underscoring the urgent need for evidence-based policies and interventions that foster meaningful social connections across the life course. Social connection is not a luxury—it is a health imperative that must be embedded in all levels of policy, care, and community life. This requires urban planning that creates third places and walkable neighborhoods, workplace policies supporting community engagement and work-life balance, education systems teaching social and emotional skills, and healthcare systems addressing loneliness as seriously as other health risks.

Short-term group psychotherapy to reduce loneliness using established techniques to target negative biases has shown promise. Addressing the cognitive distortions that maintain loneliness—the negative expectations and interpretations that prevent positive social experiences—may be necessary for those experiencing chronic loneliness before social opportunities can help. This suggests that effective interventions must combine psychological treatment to address distorted thinking with practical opportunities to form connections and community infrastructure supporting sustained relationships.

The silent loneliness epidemic nobody talks about is killing more people annually than many recognized public health crises, affecting one in six people globally with accelerating prevalence, causing serious physical and mental health consequences, operating through complex biological and psychological mechanisms, disproportionately affecting young adults and men while cutting across all demographics, and remaining invisible due to stigma and lack of recognition as legitimate health issue requiring intervention.

Breaking the silence requires recognizing loneliness as public health emergency, reducing stigma through open discussion, implementing screening and treatment protocols, rebuilding community infrastructure and third places, addressing the technological and social forces driving isolation, and fundamentally reconsidering social policies and urban design to prioritize human connection as essential to health and survival.